Members of the CCA are involved in many ways, sometimes including social protests like this one in Charleston, W.Va. in 2017.

As the Catholic Committee of Appalachia celebrates 50 years, young leaders keep looking ahead.

What might the future of the Catholic Committee of Appalachia (CCA) look like? That was the question that a younger generation of churchworkers considered at the recent 50th anniversary of the groundbreaking organization. “A lot of the ideas we had were really largely rooted in community. That is a hunger that I’ve heard in personal conversations with several other younger members of CCA,” says Sarah George, who operates a volunteer program, Emmaus Farm, in Lewis County, Kentucky.

Sarah George, director of Emmaus Farm and member of CCA.

Not so long ago a Glenmary volunteer, she’s a CCA leader, currently serving on its board of directors. She hears that longing for community support from other workers in Appalachia, saying, “Whenever we do any sort of meeting or annual gathering, I feel like the first and last things we all say to each other is, ‘We need to do this more often.’”

The CCA was always a combination of loosely-knit friendship and support, and has a history as a collaborating spot for Appalachian social-justice causes. Members are connected in some way to the Catholic Church scattered across the Appalachian portions of 12 states and all of West Virginia. Michael Iafratta, one of two staff-members for the organization, says, “there’s something distinctive about what we’re called to do as the Church in the Appalachian region. It’s always changing, because the region is always changing.” The challenge today, he says is to ask, “What is the Church called to do and be in the Appalachian region? How do we learn from each other?”

COVID-modified

“It was quite the undertaking, but we had a lot of fun putting it together.” That’s CCA President Ed Sloane, speaking of the COVID-19-modified 50th Anniversary celebration. Ed, Sarah, Michael and others, confronted with the sudden pandemic shutdown, took the ball and ran with it. They organized and conducted online Zoom conferences with various talks over a four week period this past September and October, including an evening with the “elders” (as the younger members call those people from the 1970s). There was a film about the region, a streamed liturgy led by Diocese of Lexington Bishop John Stowe, a breakout session of younger members and a series of topical panels.

The idea was to nurture community, and thus to “empower CCA members to be church in their communities,” says Ed. “CCA is a member-driven organization.”

A list of the types of folks who share membership of CCA gives a flavor of who’s driving. There are groups, such as Kentuckians for the Commonwealth, that confront legislative policies that favor unethical corporate behavior. These include, to name a few, ruining local drinking water, removing the tops of mountains in pursuit of coal, releasing toxins into the environment.

There are literacy programs, nurses who operate clinics, farms demonstrating sustainable agriculture, advocates for ecology concerns in the spirit of Pope Francis, a network of nonprofit housing construction companies that have literally built thousands of homes, anti-opioid advocacy groups, and many more. “CCA members are encouraged to bring their faith into local movements for justice,” says Ed. “These local engagements shape CCA’s agenda for collective action.” CCA currently has three hundred members, with state chapters in Kentucky, North Carolina, West Virginia, and Tennessee.

Longtime member Carole Warren, an educator who has deep family roots in West Virginia, wrote an essay for Catholic News Service this past August describing how CCA has supported her own work in a local literacy program over the years. “In joining CCA, I gained a network of experienced Catholics ministering in the area, endeavoring to employ a more respectful model — encouraging local people to use their own skills to help their communities prosper.”

That humble, listening approach among her CCA friends, not “do-gooders” coming into the region with all of the answers, is what first attracted her, she wrote: “Don’t assume, consult. When in doubt, ask. Don’t do it yourself, collaborate. And collaborate we did, expanding a network of successful projects and a forum for advice and sharing.”

Carving a future

“I think that the younger generation is taking on the reins now,” asserts Sarah. Both she and Ed are mid-30s or younger, which bodes well for the future of CCA. “We have the benefit of having the 50-year history and tradition before us. We ask, How did they live out this mission for 50 years?” One concrete way is to look at the pastoral letters, she says, particularly the one in 2015 that best expresses community interests today. “They give specific guidance of what it means to be a prophetic voice, and what it means to work for justice.”

There is a longing among newer CCA members for connection outside of their local projects. There will be more Zoom meetings in the future, more frequently. It’s possible, and easy to achieve. “In CCA I get to be around other people who are actively and tirelessly doing their own ministries.”

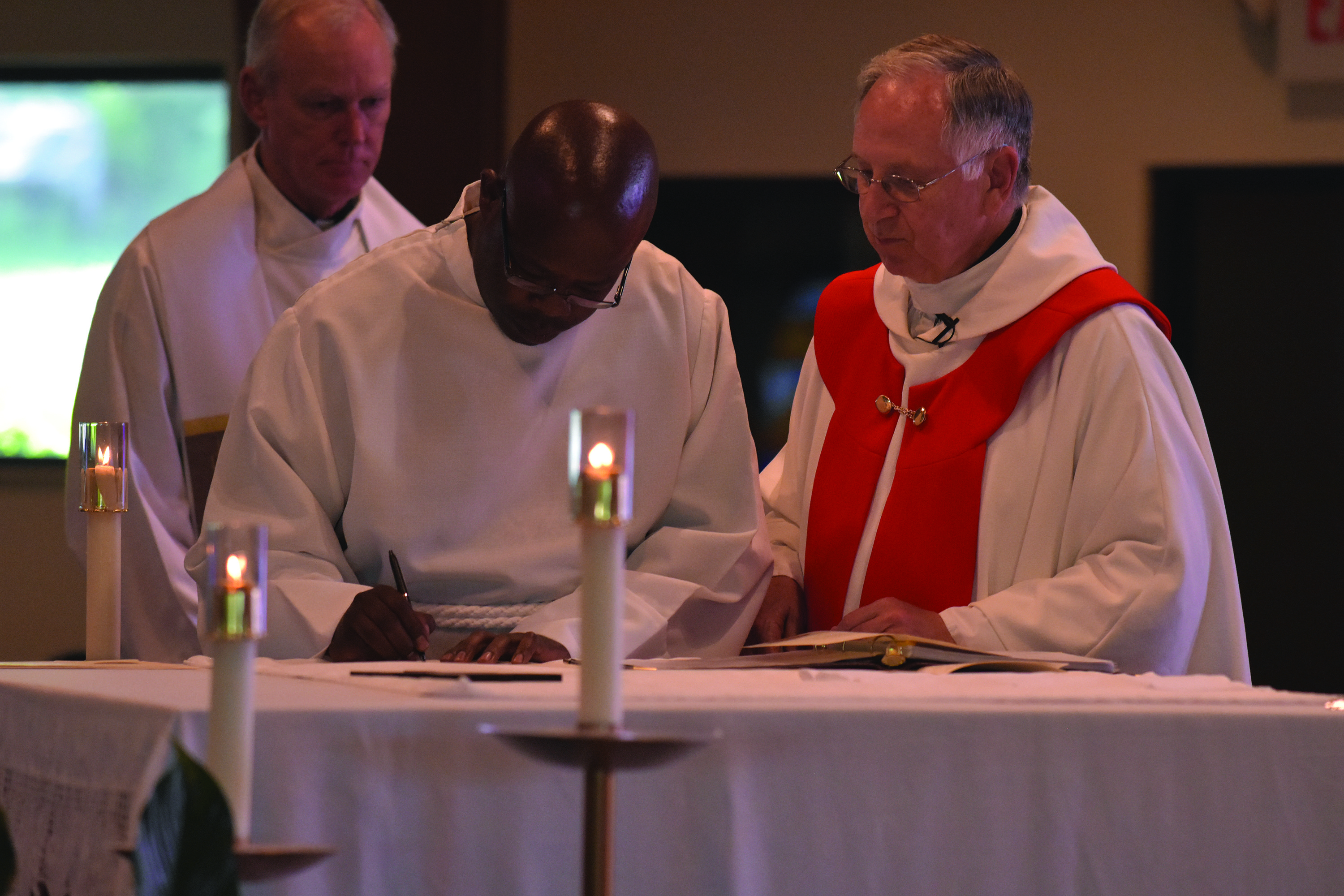

The late Glenmary Father John Rausch, right, was a key player in CCA for decades, seen here with Todd Justice at an African American heritage center in Eastern Kentucky.

New advocacy and other programs will follow from that. Care for the Earth, since the very beginning a concern of CCA members, is a good example. The sharing and doing of ideas, listening, responding, listening again spawns social change. That’s as true for confronting coal-extracting mountain-top removal as it is for building solar-powered houses. It started with sharing friendship 50 years ago, and it will continue that way.

Lexington’s Bishop John Stowe is confident of that: “The Catholic Committee on Appalachia is really teaching the church what it means to form community,” he tells the Challenge. “It is a vital expression of the church at the grass-roots level.”

He calls to mind CCA’s latest teaching, the People’s Pastoral, “a listening process. What is heard is distilled and discerned, and the guidance of the Holy Spirit points the way. In this letter, the Magisterium of the Poor and the Magisterium of the Earth come together beautifully.”

That new style of authoritative teaching, from the ground up, along with the advocacy and community organizing that follow, is one part of what makes CCA tick. Those community-building, future-dreaming get-togethers are the other.